Page 2 of 11

Introducing user centred research

In the previous module, we looked at all the different elements you need to think about at the beginning of the process of design and development in healthcare. If you’ve followed this process yourself, you’re likely to be at the stage where you’re ready to start actually designing and developing your product. We use an iterative process for this. User-centred research is fundamental to this process, and will be the focus of this module.

This is the process we follow when carrying out user research:

- Establishing objectives and outcomes

- Identifying core research questions

- Planning research methods

- Engaging participants

- Meeting ethics requirements

- Recruitment

- Consent

- Doing the research

- Analysis

- Reporting and dissemination

…and is of course influenced to some extent by all of these.

People are surprising, contradictory and complex. It is always best to start with the assumption that you can never easily guess how a user will behave. Let’s look at why in more detail.

Rational humans?

The assumption that human decisions are always rational, or that what is rational for one person will be equally logical for another, has been largely challenged over the past decade. As Dan Ariely points out in his book Predictably Irrational: “everything is relative”. People often don’t know what they want until they see it in context. Priming, anchoring, and framing are key to how we respond to choices we make. People like to compare things that are easily comparable, and the context of how we present items heavily skews our response to them.

Super social species

Humans are also a “super social species” whose behaviour is unconsciously influenced by what other people do - “herd behaviour”. This happens more so than we realise or like to admit. When faced with uncertainty we look to how other people behave and will often follow their lead.

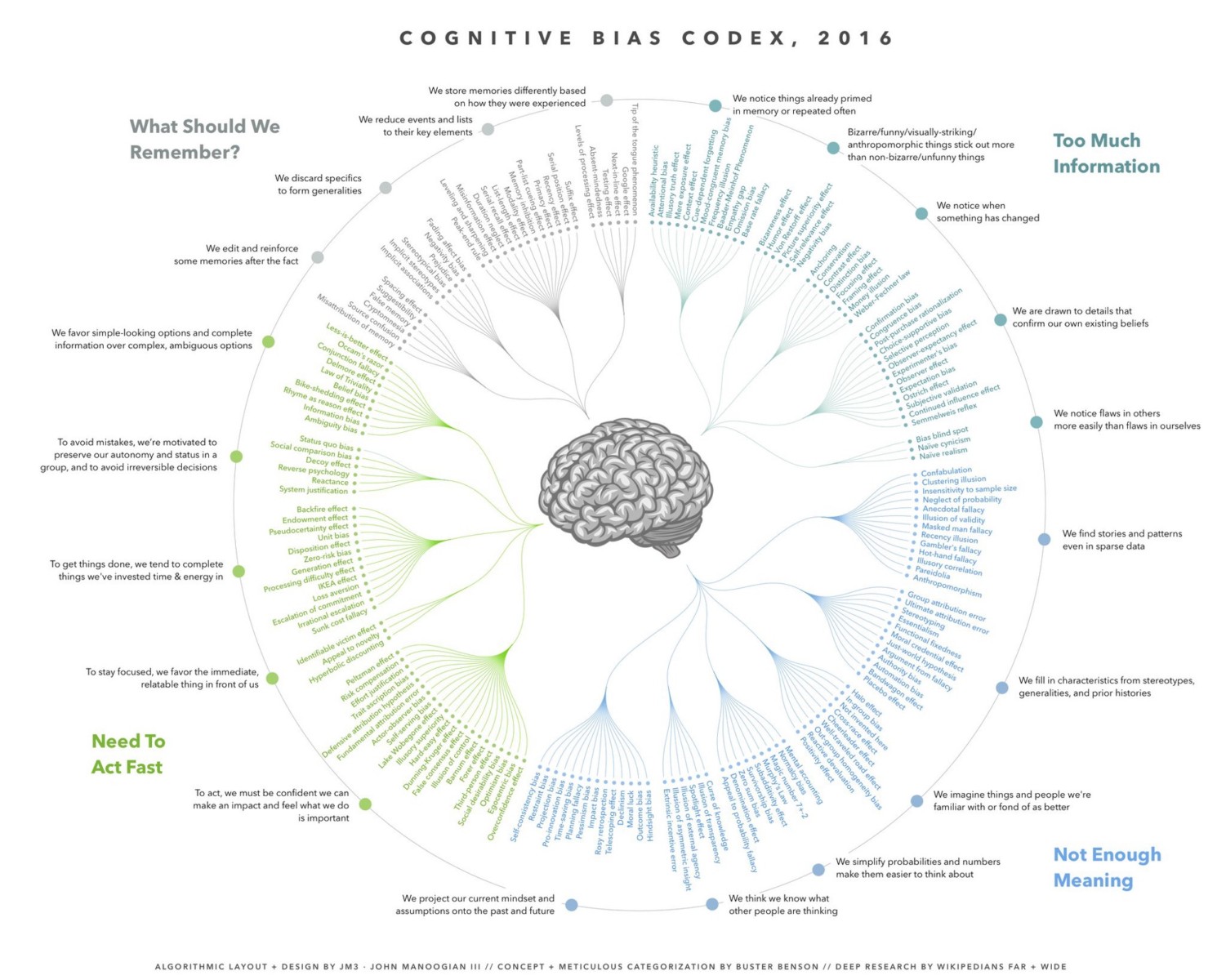

With this in mind it is useful to think about cognitive biases (the systematic errors of judgement that humans are prone to) and how they can influence behaviour. These are often completely unconscious and surprising to people when revealed. A few interesting ones to reflect on are:

Confirmation bias: Humans tend to focus on information that confirms what they already believe and discard anything that might disagree. From Leo Tolstoy, in his essay “What Is Art?”:

“I know that most men—not only those considered clever, but even those who are very clever —can very seldom discern even the simplest and most obvious truth if it leads them to admit the falsity of conclusions —conclusions of which they are proud, conclusions which they have taught to others.”

Sunk cost fallacy: This refers to the tendency to throw good money after bad ie. feeling more inclined to continue to plough money into something when you’ve already spent money (or other resources) on it, even if it’s not worked so far.

Arkes and Blumer (1985) ran studies in which participants were put in charge of research budgets. They found that people were far more likely to continue to spend on an investment when told that they significantly invested in it in the past. This was in spite of the previous investment failing. This is an easy trap to fall into in a project, many of the decisions that affect individual health and patterns behaviour can be traced back to sunk costs.

Cheerleader bias: This is the name given to the perception that individuals in a group are more attractive than individuals in isolation, as demonstrated by recent research at the University of California. Current theory suggests that this so-called ‘cheerleader bias’ is caused by:

- The visual system automatically computing ensemble representations of faces presented in a group

- Individual members of the group being biased toward this ensemble average

- Therefore individual faces are perceived as being more attractive because they seem more like the ‘average faces’ that we naturally find attractive

Psychologists have studied a range of cognitive biases which influence human behaviour. You can read more here.

In summary, when we are thinking about individual decision making we should try as much as possible to understand the complexity, plasticity (or adaptability) and context of the people we are working with.

The changing history of user research

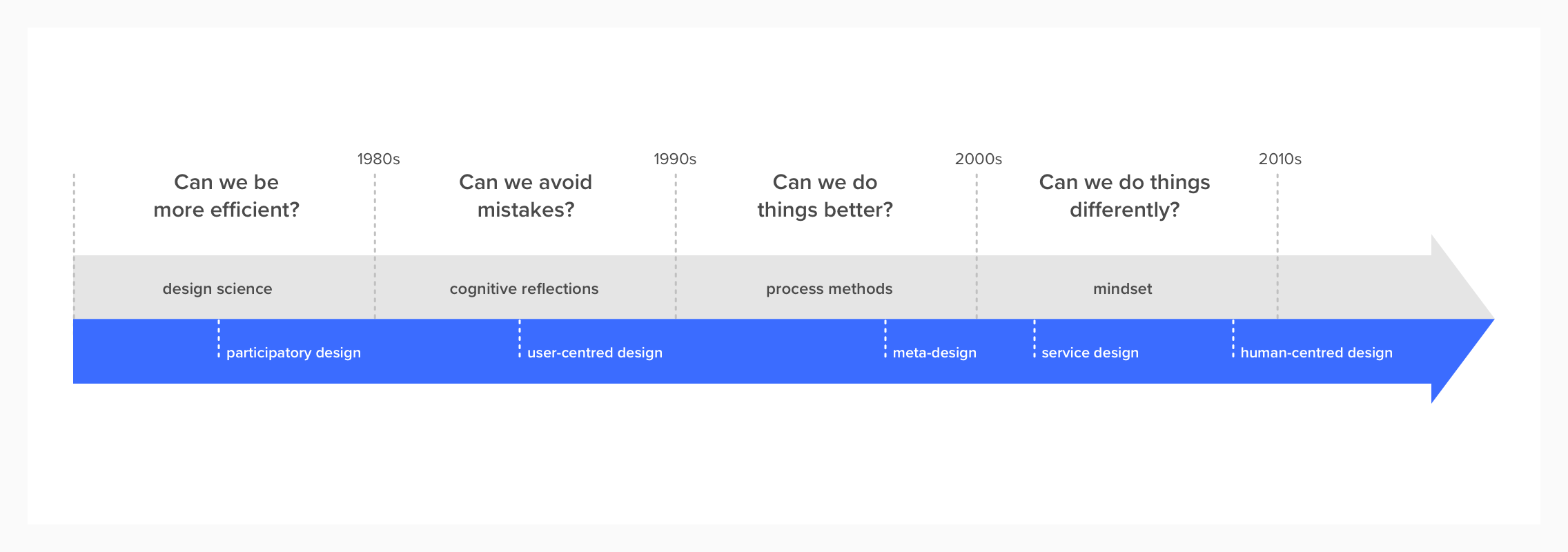

Before doing user-centred design research, it is worth learning about the history of user-centred design research. Understanding the evolution of this discipline can help to appreciate why it is important. The timeline here gives you a rough outline of the history of user centred research, with the broad areas of development over time. It began with the rising adoption of computing, which required new thinking about design, and in particular the interaction between humans and machines.

Lucy Suchman, Dan Norman

Lucy Suchman, an anthropologist first employed by Xerox Park in in the late 1970s, was a key figure in setting up the field of Human Computer Interaction (or HCI) with her book “Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-machine Communication”. Her application of ethnographic research methods was a revolutionary step to reveal the subtle ways in which interactions between people and technology can never be taken for granted.

Over time, design thinking around this HCI field became increasingly sophisticated, with the focus moving onto the way in which design can facilitate this interaction (see Dan Norman’s 1993 book: The Psychology of Everyday Things, for example). If design is a facilitator, then the designer needs to think about how to do this in a way that makes this process easy or even pleasurable for the user.

User-centred research and design techniques are therefore at the heart of this, to understand user needs and behaviours, and the impact of design decisions on this. We’ll outline some of the ways we do this in product development processes over the rest of this module. Interestingly, there has been emerging research that may shift this thinking again, suggesting that the focus on the user is too individualistic and ignores systems, networks and context. There has also been some interesting recent thinking about participation and inclusion in design research. been some interesting recent thinking about participation and inclusion in design research.

Diagram above adapted from here.

Diagram above adapted from here.